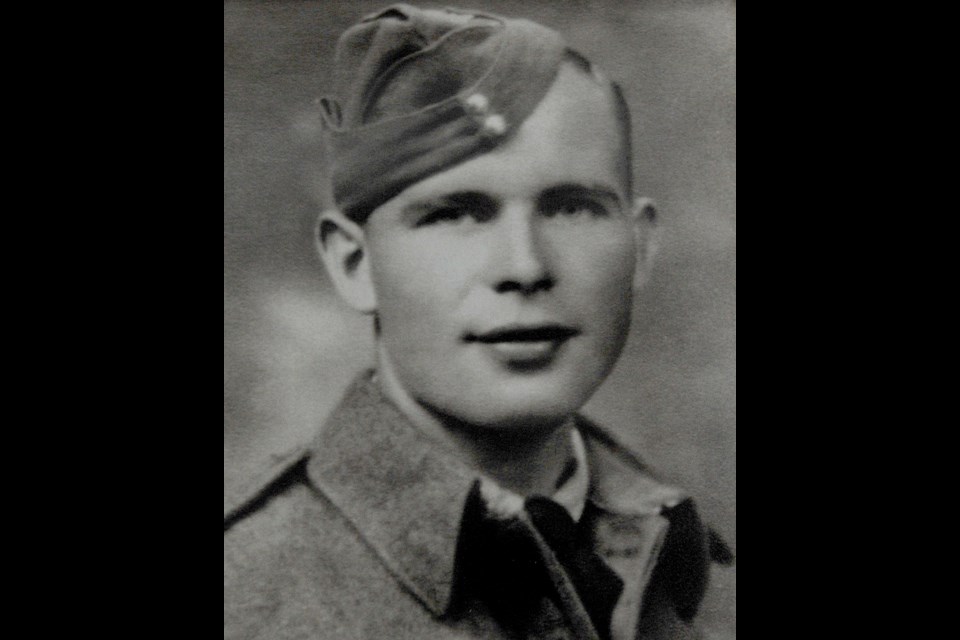

William Snow wasn’t about to miss an opportunity.

The Second World War veteran is always prepared to honour his buddies on Remembrance Day and this year would be no different. But not, due to COVID-19, during the typically well-attended mass gathering at the Barrie cenotaph.

The spry 98-year-old Barrie resident is the only member of Canada’s military in active duty during the 1939-45 conflict to be invited to a special gathering on Nov. 11 at the Royal Canadian Legion Branch No. 471 near St. Vincent Street and Cundles Road.

Snow enlisted at the end of 1942, when war was ravaging cities and the countryside of Europe.

“I was a private for the artillery. I drove a truck for the 1st Canadian Radar Battery,” he proudly tells BarrieToday during an interview from his east-end home. “I was a driver and we spotted targets for the artillery in France, Belgium, Holland, Germany.

“If the infantry were having a rough time being pinned down with mortar fire, we were called in and gave (the artillery soldiers) their targets.”

It was dangerous work.

“Of course it was! There was a war on. It was always dangerous. There was no part of it that wasn’t,” Snow says. “I do have lots of things I could tell, but I don’t talk a lot about it. But my memory of those days is just as good as it was back then 70 or so years ago.”

In her book, No. 1 Canadian Radio Location Unit and Radar Battery: WW II 1939-1945, author Lorne Verdun Phillips detailed some of the duties of Snow’s comrades.

"While in Northwest Europe, (the) Radar Battery served with all the advancing fronts. The radar units picked up enemy mortar bomb signals and relayed this information to the (Allied) artillery, which would attempt to silence the enemy mortars. This they did through Belgium, Holland and into Germany until the war ended officially on May 8th 1945."

Joining the Allied effort “was the thing to do," Snow says.

“Why did I enlist?” he asks himself while laughing. “Sometimes I wonder why I enlisted. That would’ve been a silly question at the time.

“I felt it was the thing to do, that’s all. It certainly wasn’t for the money we were earning at the time (in the military),” he adds, still chortling.

“My parents definitely didn’t want me to enlist; I was the only son. I had five sisters, so my mother definitely wanted to keep me around. However, that’s another story.”

Reflecting on sacrifices made in the past during Remembrance Day is something Canadians of all ages can — and should — do, Snow adds.

“Actually, I think it’s more important now than maybe it was 30, 40 or 70 years ago. That’s the way it seems to me now, today,” he says. “When you stop and think about it... for instance in Holland, they still celebrate the freedom we gave them 75 years ago.

“They still love us and that is one reason for them (to reflect) and for us as well. That’d be the reason for enlisting.”

He also say that whether it’s 100 years ago or 10 years ago, sacrifices made during service to Canada are, and always will be, important.

“If we want freedom — and we want to remain free — we have to do something about it; we have to keep it. If you want to be free you have to pay a price,” Snow says, adding young people should be encouraged to reflect on the sacrifices made by Canada’s military men and women.

“Maybe they should know what we did and be thankful for the life they have now, the freedom they’ve got," he adds.

Fern Taillefer, of the Royal Canadian Legion Branch No. 147, says the organization is having invite-only events (with all the required COVID restrictions in place) on Remembrance Day and that Snow would not be denied an opportunity to attend.

“He was so insistent when I told him we weren’t going to invite (the general public), he said, ‘I want to be there’,” Taillefer says. “So I said, ‘Well OK’. I can’t say no to a World War Two veteran.

“When you think about it, he was there. He lost friends there and that (the legion event) is his own way of remembering his friends and thank them for what they have done.”

Snow says his contributions to the war effort weren’t any more vital to the Allied victory than those of other Canadians.

“Maybe I have it wrong, but the the way I figure it is that during the war, the people that were, say, making the ammunition here in Canada (or other war-related jobs), everybody had a job to do and one was just as important as the other one,” he says.

“Wherever they thought you were needed, that’s where you were.”