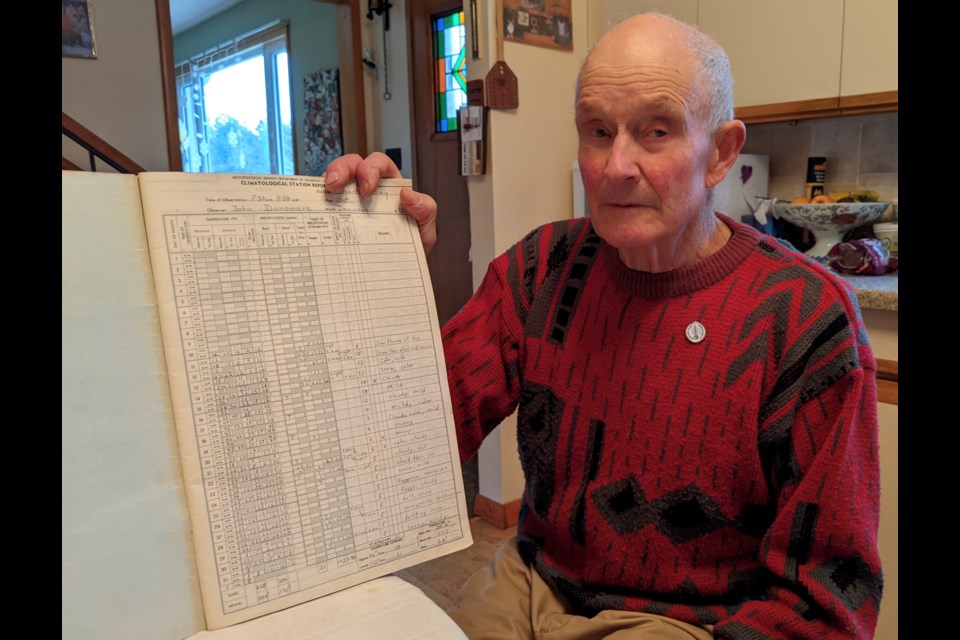

It was 50 years ago that John Dunsmore first began tracking local weather.

Since Jan. 10, 1973, maximum and minimum temperatures, plus precipitation, have been recorded each and every day at Dunsmore’s property near the municipal border between Barrie and Oro-Medonte Township, just off Ridge Road, with help from his wife, Rosemary, along with daughters Joan and Lori.

“Let’s say it gives you a warm feeling,” the soft-spoken 83-year-old said of his long record-taking.

Dunsmore said he took to heart the advice of his younger brother, Hugh, a scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, the national organization for geoscientific information and research, on how to track the weather.

“He told me for these records to be of any use, don’t miss a reading,” said Dunsmore. “If you go away for the weekend, have somebody do it because if it’s not done it’s worthless.”

The Dunsmore property is nearly 140 acres, covered in trees, but until a dozen years ago it was a beef farm.

How does a beef farmer become a weather tracker with Environment (and now Climate Change) Canada, a volunteer position that necessitates recording temperatures and precipitation twice a day, rain or shine, thaw or freeze, in all four seasons?

The Dunsmores subscribed to the Winnipeg Free Press and read a story about a Manitoba beef farmer who had a weather station. There was contact information for anyone interested in doing the same.

“This farmer in Manitoba described what he was doing and it sounded very interesting,” Dunsmore said. “I was always interested in the weather before this, because every day I had to work in the weather and with the weather, and I worked in the bush in the winter time, cutting firewood, logs."

Dunsmore got in touch with Environment Canada and felt he made the grade.

“They were looking for a small farmer that was there all the time, never went away because he had to attend to his animals, and I fit the bill, exactly what they wanted,” he said. “They came and interviewed me and then decided this is where they’d put it (the station), so they came out and we set it up.”

Environment Canada visited what's called the Shanty Bay weather station annually to check the instruments, the thermometers and the rain gauge to be sure there were no cracks and that everything was working well, Dunsmore said.

And the rules were rigid.

“The thermometers can’t be within the shade of a tree and same with the rain gauge, because some of the rains are driving rains, with the wind,” he said. “If a tree is close by, it will affect your measurements.”

But brother Hugh’s experiences with the Geological Survey also convinced Dunsmore how important it was to track the weather.

“He spent a couple of summers on the High Arctic islands and he was astonished with what he saw,” Dunsmore explained. “This was in the 1980s, the ice melting at a very rapid pace at that time and he came home with some butternuts and some pine cones which had melted out of the ice. They had perhaps been there six, seven thousand years. He didn’t know how old these things were.”

Dunsmore said his brother was also fog-bound there for a week.

“The fog was so thick you couldn’t see your hands in front of your face. It was because of the warm weather," he noted.

It was another argument for the truth of climate change, to Dunsmore’s thinking, and it gave him another reason to track the weather.

And he practises what he preaches, especially on his property.

“It’s now been planted all out in trees because I thought, for one reason, that trees are the best way to fight climate change,” he said.

Dunsmore still keeps the twice-daily records on temperatures and precipitation in books, called the climatological station report, in part because he doesn’t trust computers to do what pen and paper have done for all these years.

John Dunsmore has been recognized by Environment Canada for 20 years, then 40 years of service.

Fifty years should certainly be next.